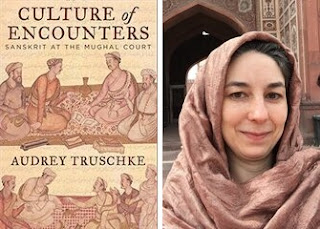

Author: Audrey Truschke

Publisher: Allen Lane, 2016 (First)

ISBN: 9780670088942

Pages: 362

India’s

language and culture underwent great changes during the six hundred years of

Islamic invasions and occupation. An oligarchy attached to the rulers and who

had no roots in the country subjected it to autocratic rule. Earlier, Sanskrit

served as the link language on its position as the primary medium of literature

all over the subcontinent. With the advent of the Sultanate and later Mughal

dynasties, Sanskrit fell from grace. The sultans co-opted Persian as the court

language. After Mughal power was consolidated during Akbar’s reign, he looked

for ways to establish post-factual legitimacy by understanding and assimilating

traditional royal claims to the throne. With this requirement in mind, they

translated epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata and a few other works into Persian.

This book is a case study of how the Mughals engaged with Sanskrit texts,

intellectuals and ideas and how Sanskrit scholars responded to and participated

in this demand for Indian stories, practices and philosophies. It deals with

Sanskrit at the Mughal court from 1560 to 1660 CE, that is, from the reign of

Akbar to Shah Jahan. A few minor works are artificially enlarged to match with

the author’s high assessment of its worth and impact. The book also accepts

that Sanskrit tradition collapsed entirely by 18th century. Audrey

Truschke is an assistant professor of South Asian History and is the author of

two controversial works on Indo-Islamic interactions. Her book on Aurangzeb had

received much criticism in its dishonest handling of descriptive sources to

paint the bigoted sultan in an admiring light.

Akbar

declared Persian as the official language of his empire in 1582. Even before

this event, Mughal court had extended lavish patronage that attracted Persian

poets, thinkers and artists from across Asia. With this virtual takeover by a

foreign tongue, little space was left for Indian languages. However, Akbar

sensed the disconnect this move had engendered with the numerically majority

community of India. With this in mind, he initiated links with the Sanskrit tradition

that were concentrated around the central court. Akbar sponsored the

translation of many Sanskrit texts into Persians, hosted dozens of Jain and

Hindu Sanskrit intellectuals at court and hired Sanskrit-medium astrologers.

Initial Mughal engagement with Sanskrit was about music and dance. Akbar very

much enjoyed Indian performance traditions. However, the favourite theme of

court poetry centred on eroticism. The title of one such treatise if ‘Akbar

Shahi sringaradarpana’ (mirror of erotic passion for Shah Akbar). This book

devoted bulk of its attention to the erotic mood and typology of heroines.

Mughals were voracious readers of such concepts in other languages like Hindi,

Arabic and Persian too. Such were the subject matter of original books composed

during this period.

The Sanskrit intellectuals in Mughal court were not

solely interested in translation or helping Persian scholars gain insight into

Indian treatises by explaining their meaning in the vernacular language.

Truschke claims that Hindi had become the most common vocal language of the

palace. Perhaps she means Urdu, as the Braj Bhasha was still not used by Muslim

aristocracy. The Indian scholars also managed to gain a few meager political

concessions due to their proximity to the sovereign. Jain monk Hiravijaya

elicited from Akbar a prohibition of animal slaughter during the Jain festival

of Paryushan. Similarly, a punitive tax on Hindu pilgrims visiting Varanasi and

Prayag was rescinded for a while. But it seems that nobody took these

prohibitions seriously and nothing changed on the ground as we see Jahangir

reissuing the same injunction a quarter century later. Their position at court

was not secure either, depending solely on the whim of the emperor. Mughals

occasionally grew suspicious of the Jain doctrine as harbouring atheistic

notions. Atheism was such a serious offence to Mughal sensibilities that even

Akbar was not prepared to countenance it. Jahangir banished all Jain monks from

the empire and stopped the stipend of his Jain court scholars by 1620. Some

scholars moonlighted as court performers. Kavindracharya Saraswati and

Jagannath Panditaraja were renowned Hindi singers as well. The author claims

that development of vernaculars led to the gradual eclipse of Sanskrit.

The

book displays the entire spectrum of Sanskrit literary work other than

translation of epics in the time of Akbar and translation of philosophical

texts like Upanishads commissioned by Dara Shukoh, a truly India-minded Mughal

prince. Other genre included hagiographies such as Allopanishad (Upanishad of Allah) penned in the Vedic style on

Akbar’s own request. This work alluded to Akbar’s status as a prophet. The

vassal rulers imitated the fashion in the central court in the form of sending

Sanskrit praise poems to the Mughal court. Rudrakavi, a Deccani king’s

courtier, created panegyrics for Jahangir, his brother Danyal and son Khurram -

later Shah Jahan. The rulers did not understand Sanskrit, but these were

primarily intended as gifts rather than a literary article to be read and

understood.

This

book is the product of a clever agenda to present the period of Islamic

occupation of India as something beneficial and benevolent to India’s culture.

The very need for such highly organized and heavily financed high-decibel

campaign provides the answer to the question of how it affected Indians.

Through the translation of Indian texts into Persian, the Mughals had had some

definite plans in motion. The translators often bitterly complain about their

unsavoury task in having to handle a religious text of the unbelievers. Akbar had

Mahabharata translated into Persian as Razmnamah

(Book of War). Mulla Shiri, a translator in the project, characterized the book

as ‘rambling, extravagant stories that are like the dreams of a feverish,

hallucinating man’ (p.110). Abul Fazl was instructed to write a preface to the

Mahabharata against his will. So, he remarked in the preface that the

translation is intended to bring the religious texts in a clear, expressive

language intelligible beyond elite circles, so that simple believers would

become so ashamed of their beliefs that they will become seekers of truth

(Islam) (p.131). Badauni refused outright to write a preface to his own

translation of the Ramayana, denoting it to be a ‘rotten, black book’. Badauni

even writes out the Islamic profession of faith in the translation and begs

Allah to forgive him for translating a ‘cursed book’ (p.138). The content of

the texts were also altered to suit the need. Praises of Akbar were made to

come out of the mouths of the heroes of epic poems! The Islamic god was

inserted into a supreme position in the Mahabharata translation and Hindu gods

were preserved as mere intermediaries between humans and Allah. This is

replicated in the Ramayana translation also. The Bhagavad Gita is condensed

into a barebones sketch of the conversation, eliminating most of the source

version’s abstract reflections and philosophical concepts.

The

book is replete with gross exaggerations and conclusions disproportionate in

magnitude to the available evidence. Just because the Mughals had encouraged a

few intellectuals whose number can be counted on the fingers of our hands, it

does not mean that Sanskrit was a part of the Mughal cultural milieu. Truschke

then makes a leap of wishful thinking and claims that this suggests a

multicultural imperial context. In fact, the real seeds of development of

Indian culture grew outside the Mughal court, often in fear of royal

oppression. Persian court texts very rarely mention the Indian scholars or if at

all, portray them as marginal figures of no consequence. Only Hindus and Jains developed

bilingualism by learning Persian while even Indian Muslims did not study Sanskrit.

Other than classical works, only very insignificant books were produced after nearly

a century of ‘encouragement’ and very few copies survive in manuscript form. Glimpses

of Truschke’s pet program of glorifying Aurangzeb’s hate-filled actions are seen

in this book also. His withdrawal of encouragement to Sanskrit is described as ‘a

sensible political act’ in view of his rivalry with Dara Shukoh. Oxymoronic statements

like ‘Sanskrit was an undeniable part of Mughal court culture, and yet the language

itself remained grammatically inaccessible’ betray the lack of careful analysis

of facts. Readers also encounter pompous statements like ‘I stand on the shoulders

of many giants in shaping this book’ undeservedly presuming that this is a masterpiece.

Last time we heard this statement was from Isaac Newton commenting on his ground-breaking

discoveries on gravity and calculus.

The author

repeatedly stresses on the term ‘multicultural’ to characterize the Mughal court.

In every chapter, you see it used again and again as a form of conditioning the

reader. A glance at the number of individuals and texts in each courtly language

would expose the fallacy of this argument. The book includes a chapter on Abul Fazl’s

Ain-i-Akbari which introduced Indian and Sanskrit literary concepts to the Persians

in a comprehensive way. The author unduly pits the Jains against Brahmins and Rajputs

by exaggerating scholarly and professional jealousies common among competing intellectuals

in a royal court to the level of bitter enmity. This fight is then portrayed as

moderated under the benevolent gaze of the Muslim rulers. The book is a drag on

readability due to its complex formation of sentences and ideas.

The book

is recommended only for serious readers.

Rating:

2 Star