Title:

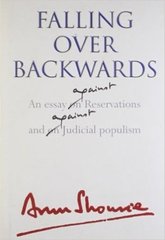

Falling over Backwards – An Essay on Reservations

and on Judicial Populism

Author:

Arun Shourie

Publisher:

Rupa & Co, 2009 (First published 2006)

ISBN:

9788129109521

Pages:

378

When Prime Minister Vishwanath Pratap Singh announced that

he was instituting reservation for Other Backward Castes (OBC) in government

service in 1990, it was a bolt from the blue. Nobody had seen it coming and all

hell broke loose as the country plunged into a series of violent protests, in

which a few young men publicly immolated themselves to vent their anger at the

supposed loss of jobs for forward castes. The backward classes which

constituted 74 per cent of the population and the progressives among the upper

castes welcomed the initiative, while quite understandably, a section of the

people opposed it tooth and nail in parliament and law courts. The Supreme

Court finally delivered its verdict in 1993. It upheld the constitutional

validity of reservation for OBCs, but ruled that the well-off among them,

christened the Creamy Layer, should be removed from its ambit. The country

still follows that principle, while sporadic opposition to reservation

continued. By the beginning of the present century, a new trend became noticeable.

The upper castes also started the clamour for labeling themselves backward and

accord reservations to them. The Jats have almost succeeded in getting what

they wanted, while the Patidars of Gujarat are currently on the war path. Their

logic is clear. With every judicial avenue closed for repealing reservation,

and the political route impossibly difficult as the physical number of backward

castes are far more numerous, the only thing they can hope for is to crash the

gates, register all forward castes as backward and thus defeat the very purpose

of granting reservation. Arun Shourie was the editor of the Indian Express when

the Mandal agitation roiled the country. His fiery editorials and polemical

essays added fuel to the fire. Shourie still retains his strident tone, even

after all these years. This book contains his observations on reservation and

the judicial support it had received. Terming those judges who ruled in its

favour as activists and revolutionaries, he spits venom at the so-called judicial

populism.

Shourie’s attack on the backward castes of India runs on all

fronts. He treats them as non-entities, people with no talent to run government

institutions, but who wrested concessions from pliable politicians owing to

their electoral muscle. He quotes a letter Prime Minister Nehru wrote to state

chief ministers in 1961 in which he reacted strongly against reservation which

leads to inefficiency and second-rate standards. If we go for reservations on

communal and caste basis, we swamp the bright and able people and remain

second- or third-rate. Nehru adds that this way lays not only folly, but

disaster. The parting shot is Nehru’s rhetorical question on how we could build

the public sector or indeed any sector with second-rate people. Shourie builds

on where Nehru has left off by questioning even the existence of backward

castes. His argument is that the consciousness of caste came into being only

when the British started counting castes in decennial census. Centuries of

untouchability and caste oppression are just wished away by the author, who

then takes the next arrow from the quiver. Article 16(4) of the Constitution of

India, on which the entire scheme of reservation rests, envisages reservation

on appointments and posts in favour of any backward class of citizens. The

statute uses the term ‘class’ instead of ‘caste’ and about a quarter of the

book is dedicated to push this idea down the readers’ throats. Several

judgments of the apex court had clarified this issue long back. They held that

the term ‘classes’ mentioned in the constitution indeed referred to ‘castes’.

This is quite logical if a bit of thought is applied to the matter. The framers

of the constitution wanted to reserve jobs for the backward sections lagged

behind others. But, if they specifically mentioned castes in the constitution,

that’d have been valid only for that period, as there is every chance that the

plight of the backward castes might improve in the future and the need for

reserving seats for them might become obsolete. Another group – need not

exactly be a caste – may become backward by then and the provisions of this

enabling clause in the constitution can be used to provide succor to them. We

want the Constitution’s provisions to be applicable for a very long time to

come. May be it is with this intent that the makers of the constitution used

the generic term ‘class’ instead of the very specific ‘caste’? It is for the

legislature to decide which group is backward and the duty of the judiciary is

to review it. Both have done their jobs well, but the author accuses them of

populism.

The book includes some prescient remarks that highlight the

shrewdness of the author. He rightly surmises that if individuals and groups

get rewarded on the basis of their being different from the rest, leaders will

foment a politics that exacerbates the difference (p.33). That such an

insightful scholar let go of absurd notions as well may surprise the readers.

The hypothesis that castes in British India were in a state of flux is one

such, especially with exodus of rural folk to the cities. Shourie’s point is

that ‘in towns, it was quite easy for a low-caste person to claim a higher

caste without any fear of detection’ (p.56). So, that’s it! The only way

out for a person of backward castes to gain some dignity is to masquerade as a

high-caste one in a far-off town! Elimination of the comparatively better off

among the downtrodden communities has been a strong demand of all those who

opposed reservations. Unfortunately, the passion of petty jealousy which

underpins this idea remained unnoticed in the judicial review and the court’s

reason for exempting the creamy layer was that reservations were to be for a

class. To be a class, the group must be homogeneous. When some in it are

clearly different from the others, it loses the character as a class. Besides,

unless these advanced persons are excluded, they’d hog all the benefits that

legislation may seek to provide to the backward classes. But, eliminating such

a big chunk of eligible people from the purview of reservation has made it

partly ineffective. It was reported recently that less than half the seats

reserved for OBCs were actually filled in the last quarter century in which

reservation was in place.

Shourie treats the backward castes as subhuman morons as he

pities the condition of the administration where half the posts are manned by such

people having no qualifications for the job. His contemptuous duplicity fails

to mention that all candidates – irrespective of whether they are backward or

not – must qualify the basic criterion say, a degree. There is no relaxation to

the backward castes in that. It is only in the screening process that some

allowance is made. However, screening is not an essential part of selection. If

the total number of candidates is less than or equal to the number of

vacancies, everyone would be selected without further screening, provided they

have the prescribed academic qualifications. Can we say that people appointed

thus are not qualified enough or not talented enough? Shourie himself admits

that not enough candidates from reserved categories are found. According to his

own data, in 1992, the medical officers of UP from SC/ST communities comprised

only 6 per cent of the total, whereas 20 per cent was earmarked for them as reservation.

Most of the quota remained vacant, but the author fumes over promotions granted

to them. Shourie breaches his leash and jumps at the judges with foaming mouth

as he accuses them of populism and playing into the hands of opportunist

politicians. His choicest invective are reserved for Justice V R Krishna Iyer.

The book is good reading for those who want to follow the

court verdicts against finer aspects of reservation and how the legislature

bypassed it by amending the constitution. However, finding the useful

information from the sea of irrelevant rant will be a herculean task. Many

points and ideas are needlessly repeated with detailed nitpicking of court

rulings and judgments reproduced verbatim. It is plain boring at such times.

The book is written in a propagandist style with absolutely no wit or humour.

The author is always in a state of rage right throughout the entire text. This

can be expected when you feel that what you are saying is not convincing to the

people who hear it.

The book is not recommended.

Rating: 2 Star

No comments:

Post a Comment