Title:

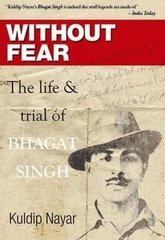

Without Fear – The Life and Trial of Bhagat Singh

Author:

Kuldip Nayar

Publisher:

HarperCollins, 2007 (First published 2000)

ISBN:

9788172236922

Pages:

244

Like

the varied country India is, its freedom struggle consisted of many streams,

distinct in form and content from each other. School textbooks and government

propaganda on the independence movement harp on a lone strand among them –

Gandhi’s nonviolence. This is certainly not astonishing as the Nehru dynasty

ruled or influenced the country’s administration for most of the seven decades

it was independent. Nehru was Gandhi’s loyal protégé who was hoisted onto the

leadership of an unwilling Congress in session at Lahore in 1929 as its

president. The very first thing Congress governments did after independence was

to sanitize the history of the freedom movement by purging elements hostile to

Congress’ ideology and Nehru’s detractors from the chronicles of the country’s

fight against the British. Bhagat Singh, whose great self-sacrifice on the

altar of the country’s honour is mentioned in a bare paragraph in most of the

officially approved accounts. Many books on the martyrdom of Bhagat Singh and

his comrades found the light of day only in the last few decades. Singh’s

trajectory sparked violence and death. They were not reluctant to kill their

enemies and were not afraid to lay down their lives for the cause. Kuldip Nayar

is a world-renowned journalist who has made this excellent volume that tells

the history of Bhagat Singh’s life and trial.

Nayar

portrays Bhagat Singh as a brave and committed nobleman of integrity. Though he

was born in a family of zamindars (landlords), he was deeply influenced by the

hard toil and pitiable living conditions of his neighbours. His conversion to

atheism was deeply rooted, considering the fact that he was just 23 when he

died. Singh’s courage is exemplified by an incident on the day he was hanged

and narrated touchingly in the book. When his lawyer visited him to ascertain

his last wish according to procedure, Singh enquired whether he had brought the

book ‘The Revolutionary Lenin’

requested in an earlier meeting. As soon as the book was handed over to him,

Singh started reading it with great interest and absorption, even though he was

scheduled to be hanged a few hours later. Seeing Bhagat Singh’s portrait with a

European hat and clean shaved chin, many people are confused as to his

religion. It is incongruous to enquire about the religion of an atheist, but

Bhagat Singh was born a Sikh. He had cut off his hair and shaved off the beard

as part of the plan of disguise to assassinate the police chief of Lahore.

Though

at loggerheads with each other, Bhagat Singh’s Hindustan Socialist Republican

Association supported mass actions initiated by Congress. When the Simon

Commission was blockaded at Lahore railway station, the police baton-charged

the protesters in which the widely respected politician Lala Lajpat Rai was

seriously injured when J A Scott, the superintendent of police personally

rained blows on his head. He died a few days later which unleashed a huge wave

of resentment. Singh and his associates wanted to avenge Rai by killing Scott,

but the man tasked with identifying the officer mistook Saunders, his deputy,

for him and the assailants killed the wrong man. It was for this murder that

Bhagat Singh, Shivram Hari Rajguru and Sukhdev Thapar were handed the capital

punishment. Around the same time, the Central Assembly at Delhi was

contemplating two draconian regulations. The Public Safety bill was designed to

empower the government to detain anyone without trial, while the Trade Disputes

bill was meant to deter labour unions from organizing strikes, particularly in

Bombay. Bhagat Singh and B K Dutt threw bombs on the assembly floor in protest

against the bills, while taking special care not to cause injury to anyone. The

assembly claimed many Indian members like Motilal Nehru, Jinnah, N C Kelkar and

M R Jayakar among its members. Singh and Dutt were arrested on the spot and

later implicated in the Lahore assassination also. Many accomplices turned

approvers and the prosecution’s mainstay was the evidence given by them.

Nayar

brings out Singh’s outrage at Gandhi’s passive, nonviolent struggle in detail.

However, the jailed revolutionaries adopted Mahatma’s tried and tested program

of hunger strike to demand improved facilities in the prison such as better

food and living conditions, a special ward for political prisoners and parity

with European prisoners lodged there. While all of Gandhi’s hunger strikes

ended conveniently before it seriously threatened the leader’s health, the

revolutionaries were not so lucky. Jatindra Nath Das died of starvation. Singh

and others escaped this fate as they bowed to a Congress committee resolution

to call off the protest on the 116th day.

A

prominent part of the book is dedicated to cover Bhagat Singh’s trial, in which

the author unfortunately shakes off his reputation for critical thinking and

follows it with as much patriotism as is seen in a young initiate. Nayar

accuses the court and its proceedings to be a sham. However, this is to be

understood in conjunction with the numerous petty objections raised by the

accused that were solely crafted to obstruct and hinder the smooth functioning

of the court. Reading out loud a message of felicitation on Lenin Day (21 Jan

1930) in open court was just one of the charades. Many a times they declined

the summons and didn’t even come to the court. Rai Sahib Pandit Sri Kishen, a

first class magistrate, was assigned to try the case at first. Seeing him

ineffectual, the government transferred the proceedings to a tribunal

consisting of three high court judges Coldstream, Agha Haidar and J C Hilton

without any right to appeal except to the Privy Council. It was also given

powers to deal with willful obstruction and to dispense with the presence of

the accused. This was necessary as the visitors too often shouted in open

court. The police once beat up the accused when they refused to be removed as

ordered by Justice Coldstream. The prisoners then declined to attend the

proceedings of the court until he was removed. The government complied with

this strange demand and Coldstream was asked to go on long leave. J K Tapp was

appointed in his place and Justice Haidar was replaced by another Indian judge,

Abdul Qadir.

Gandhi

and the Congress cold shouldered the demands to save Bhagat Singh and other

accused by failing to intervene with the viceroy to commute their death

sentence to transportation for life. The viceroy was anxious to ensure Gandhi’s

participation in the Second Round Table scheduled later that year in 1931 and

the government’s compulsions were amply visible in the concessions it granted

as part of the Gandhi-Irwin Pact signed on 5 Mar 1931, just 18 days before

Singh was hanged. It was surely in Gandhi’s power to save the lives of the

trio, but his half-hearted presentation of their case convinced Lord Irwin

where his real sympathies lay. In fact, it was said that Gandhi requested the

viceroy to execute the sentence before the planned Congress session in Karachi

towards the end of March 1931 in an effort to forestall a possible demand from

the delegates to seek commutation of the sentence as a precondition to the pact

being ratified. If Singh was already hanged, Gandhi could preempt his

detractors with a fait accompli. However, we should not lose sight of the

substance behind the Mahatma’s reticence. A daring plan was being hatched by

the revolutionaries to rescue Bhagat Singh from jail, but it failed when the

bomb went off during a dry run, killing the leader of the assault then and

there. The comrades had planted a remote-controlled bomb on the Viceroy’s

Special train which again failed to cause him any injury. There was an assassination

attempt on Khan Bahadur Abdul Aziz, the superintendent in charge of the

investigation. These violent episodes might have forced Gandhi’s hand when he

requested the viceroy to commute the sentence only because public opinion ‘rightly

or wrongly’ demanded it and internal peace was likely to be promoted by it. It

failed to break the ice with the British and the three patriots were hanged on

Mar 23, 1931. Nayar reproduces Gandhi’s letter to Irwin.

However

wholeheartedly the Indian people support the patriotic fervor of Bhagat Singh,

the emphasis on violence against political opponents stirs the imagination of modern-day

separatists too. Nayar tells about a letter received from Harjinder Singh and

Sukhjinder Singh, who were awaiting their execution for assassinating General A

S Vaidya for directing the military operation on Harmandir Sahib codenamed Blue

Star. They claimed their operation to be on par with what Bhagat Singh had done

against the British. The author clearly demarcates the meaning of the word ‘terrorist’

from ‘revolutionary’ in no uncertain terms. Lines from Urdu couplets and poems

are given at the beginning of each chapter. Not providing a translation of

these verses excludes a good section of the readers not conversant in that

language from appreciating its message. The book casts some doubt on the

motives of Sukhdev Thapar who was hanged along with Singh. He is accused of deliberately

suggesting Singh’s name in the planning stages with the vile motive to get him

killed. A few letters from Hans Raj Vohra, the approver in the case, to Sukhdev’s

brother accuses the martyr of revealing crucial information to the police. The

book also includes three excellent essays written by Bhagat Singh titled ‘Why I

am an Atheist?’, ‘The Philosophy of the Bomb’ as a reply to Gandhi’s advocacy

of nonviolence and ‘To the Young Political Workers’. These articles open a

window to Singh’s sharp and critical mind.

The

book is highly recommended.

Rating:

3 Star

No comments:

Post a Comment